Insights

COVID-19 Update: Investment Implications of China’s Reopening

After infecting China, the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 made its way around the world. China is at the heart of the interconnected global economy, and these linkages facilitated the spread of the virus. Although it was the original epicenter, China appears to have been successful in suppressing the virus, though skepticism about China’s official statistics on the virus remains. After draconian lockdowns, China is now attempting to restart its economy. China’s experience offers a preview of the challenges of “getting back to normal,” and helps explain part of our equity allocations described in more detail below.

The economic damage to China has been significant. Last week, officials in Beijing announced that the Chinese economy shrank 6.8% year-over-year through the first quarter of 2020. This contraction is the first since China began reporting quarterly GDP in 1992. China’s rapid economic growth over the past three decades has made it the second largest economy on Earth. As such, the nation’s economic health is not only important to Chinese companies, but also to multinational firms from across the globe. For example, in 2019, China was responsible for 12% of Tesla’s revenue, 17% of Apple’s revenue, 19% of Nike’s revenue, and 28% of Intel’s revenue.

China’s economy has started to recover. Data released by Internet provider Baidu suggest that 90% of restaurants and 85% of malls in Beijing have reopened. Major provinces like Hubei, where the virus originated, began to lift most travel and traffic restrictions in mid-March. But China is far from back to normal. Social distancing measures remain in place, people are subject to ongoing and widespread testing, and workplaces are highly regulated. Many industrial firms now require frequent temperature checks for returning workers and mandate more than one-meter’s separation between people on production floors.

Employees at the Dongfeng Fengshen plant in Wuhan engage in social distancing while eating their lunch.

Source: Economic Times.

The fund managers we work with in China estimate that vehicular traffic has only returned to 60% to 80% of its pre-lockdown volume in major cities. Even with an immense level of social control compared to nations like the United States, China has struggled to reclaim its pre-pandemic level of economic activity. People in China and elsewhere will not return to their normal habits until they feel safe from infection.

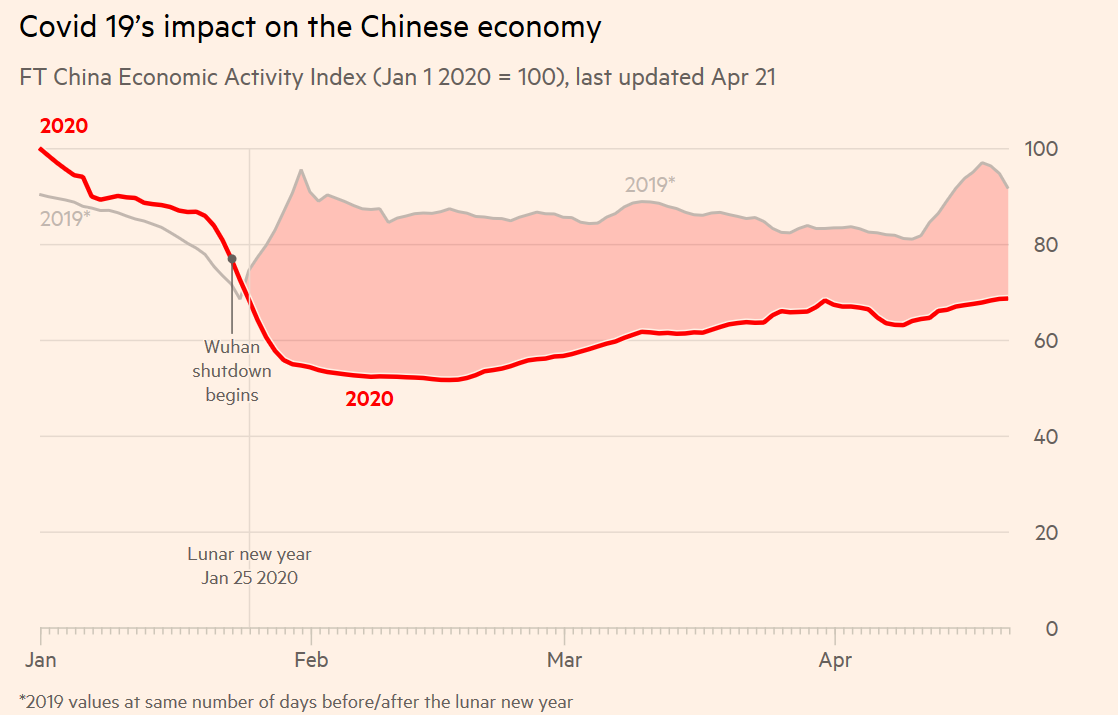

The Financial Times compiles an index of China’s economic activity from daily, industry-weighted data series. These include real estate sales, traffic congestion, coal consumption, and trade flows.

Source: Financial Times

China cannot fully recover without the rest of the world. China’s economy relies on external demand and the steady flow of imports and exports. Recently, China closed its border with Russia after a recent outbreak in the city of Suifenhe. While domestic transmission of the virus seems to be under control, imported infections continue to be reported. China’s trading partners, including Russia, have so far struggled to replicate China’s success in combatting the virus.

China’s rise is the most prominent example of how important emerging markets have become to the global economy. Over the past 15 years, emerging economies have accounted for roughly two-thirds of global GDP growth and more than half of new consumption. In 2019, the Coca Cola Company generated nearly 11% of its revenue from Latin America and 14% from the Asia Pacific region. Apple generated 7% of its revenue and Nike 13% of its revenue from developing Asian countries outside China and Japan. More than 85% of the world’s population lives in emerging nations. Of the 20 largest cities on Earth, 16 are located in the emerging world. While developed economies (and China) are aging, populations in emerging markets are young. In India, half of the people are younger than 25.

Projections for global economic growth and corporate profitability therefore hinge on the continued expansion of emerging economies. In January, before the gravity of the crisis became apparent, the IMF projected 2021 GDP growth for India to be 6.5% and the ASEAN countries (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines) to be 5.1%. The “growth premium,” or difference between emerging and developed market growth rates, was expected to increase from 2.4% in 2017 to more than 3.5% in 2023. In the wake of the virus, the IMF has slashed its projection for Indian GDP growth to 1.9% for 2021.

As the total number of infections rises, the ability of emerging market nations to contain the virus lessens significantly. According to the United Nations, roughly one billion people live in “slums” globally, with the vast majority residing within emerging market nations. Often characterized by lack of access to suitable sanitation, poor housing quality, and overcrowding, these slums present emerging economies with immense risk of viral spread and contagion. Consider the Indian city of Delhi, where population density is nearly 100 times greater than in New York City in many areas. These slums are not only densely populated, they are also characterized by indoor air pollution and poor ventilation, leaving their populations especially vulnerable to respiratory infection. A 2018 study on Delhi found that slum populations faced a 44% higher rate of respiratory influenza infection than their non-slum-dwelling counterparts, even with widespread vaccination. These countries are likely to face extreme difficulties in containing the virus.

Mumbai’s Dharavi slum, where approximately 800,000 people live inside one square mile. A resident of Dharavi with no international travel history recently died after contracting COVID-19.

Source: Economic Times.

As emerging nations grapple with the consequences of a Western financial shock and impending public health crises, their ability to effectively stimulate their domestic economies will play a significant role in any recovery. While Malaysia has announced a stimulus effort that is as high as 16% of its GDP, countries like Indonesia and India have proven reluctant to spend, only offering packages of 3% and 1%, respectively. President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil has failed to acknowledge the severity of the epidemic and has consequently resisted strong stimulus efforts. While the US and Europe have announced significant stimulus efforts that have likely reduced the prevalence of permanent layoffs and allowed furloughed employees to reap unemployment benefits, but much of the developing world has struggled to provide adequate safety nets for workers.

As a consequence, we continue to focus our equity investments on companies and regions that we believe have the most capacity to weather the shock of the pandemic. We are underweight emerging markets compared to the global stock market generally, and the emerging market stock investments we have are focused in China. We also continue to set aside some “dry powder” from our general equity allocations as insurance against longer than expected disruption to the global economy. China’s experience shows that even after the virus has been contained, the process of economic reopening will be gradual, particularly if the threat of re-infection from other parts of the world remains.